Bash Bish Falls

According to legend, Bash Bish Falls, in the extreme southwest corner of Berkshire County, draws its name from the Indian woman Bash-Bish, who lived in a village near the falls. She was well liked because of her good-looks and equally pleasant nature, but her beauty did occasionally provoke jealously from the other squaws. Eventually, this led one of her friends to accuse her of adultery against her husband. Though she protested her innocence, the village elders sentenced her to death. She was strapped to a canoe and set adrift atop the falls. The moment before she tumbled down, a halo appeared around her head, and a ring of butterflies encircled her. Frightened, some of the men went below, where they found pieces of her canoe, but no sign of Bash Bish. They concluded that she must have been a witch.

Years passed, and though stories of the incident were told, it lapsed into the background. Meanwhile, Bash Bish had left a daughter, White Swan, too young to truly remember her mother. As the years passed, White Swan grew even more beautiful than her mother, and became the wife of the chief's son, Wey-au-wey-ya (Whirling Wind). However, despite their best efforts, she remained unable to conceive, and some of the older men whispered among themselves that perhaps this was the gods' punishment to the tribe for their execution of Bash Bish. Perhaps, they thought, it might even be her own witchcraft that cursed her daughter. Reluctantly, Whirling Wind took a second wife, for it was imperative that the chief's son have a son of his own. White Swan grew increasingly despondent at her failure to bear children, eventually ceasing to leave the wigwam at all. One day, Whirling Wind returned to the wigwam to learn from his second wife that White Swan had run off toward the falls. By the time he reached the base of the falls, he saw her standing on the protruding rock platform above.

"Mother, mother," she cried out over the falls, "Mother, take me into your arms." Whirling Wind was then shocked to see the glowing, ethereal figure of a white-robed woman step out of the water beneath, stretching out her arms to White Swan. Panicked, he began clambering up the rocks to the platform. She turned to look at him.

"Wey-au-wey-ya, my brave, my chief," she whispered, and then turned back to the rushing waters. "Mother," she cried, and dropped forward into the waterfall. Crying her name, the brave leaped after her into the water, and was lost. Later, the chief and his men found his son's body, but not White Swan's. Some say that her face, and that of her mother, can sometimes still be seen in the pool below. *

***

Monument Mountain, standing between Stockbridge and Great Barrington, is best remembered as being the site of the first meeting between Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne, in 1850. The former, who was then struggling through Moby Dick, and the latter, who had just completed the Scarlet Letter, were accompanied by Oliver Wendell Holmes, who carried along ice and a bottle of champagne in his emptied doctor's bag. Melville later dedicated his masterpiece to his new friend.

Long before that meeting, Monument Mountain was known as the site of yet another native girl's sorrowful leap. A beautiful maiden from the Mahican settlement in Stockbridge fell in love with her warrior cousin, who was forbidden to her by tribal law. She tried in vain to rid herself of these feelings, but they persisted, and she grew more and more unhappy. She began to wither away. The poet William Cullen Bryant**, who based a poem on the legend, describes her spiral:

"She went to weep where no eye saw, and was not found

When all the merry girls were met to dance,

And all the hunters of the tribe were out;

Nor when they gathered from the rustling husk

The shining ear; nor when, by the river's side,

They pulled the grape and startled the wild shades

With sounds of mirth."

Eventually, she could bear no more torment. She dressed herself in her finest jewelry and ornamentation, wove flowers into her hair, and made her way up the mountain, where she climbed up the face of the pillar known as Devil's Pulpit. She waited there until dusk, and then threw herself down the face of the cliff. It is said that her tribe buried her body on the slope of the mountain and marked it with a pile of stones (thus accounting for the cairn which can still be seen there to this day).

***

At least one version of the story of the native girl Wahconah, from whom the waterfall in Dalton gets its name, ends in a similar manner. Wahconah was a Pequot, part of a group of them who had been driven up from Connecticut. As the story goes, she was at the waterfall when she encountered a Wampanoag named Nessacus, who had made his way west after the death of his chief, Metacomet (this places the story in a more concrete historical context than the previous ones, sometime in 1676). Wahconah gave him lodging with her tribe on behalf of her father Miacomo, the chief, who was off negotiating with the Mohawks on the other side of the Taconic Mountains. Over the course of the next few days, Nessacus and Wahconah became enamored with one another. However, when her father returned, he brought with him the much older Mohawk warrior Yonnongah, to whom he had promised his daughter as wife. Nessacus challenged Yonnongah to a dual to decide who would marry the girl, but Tashmu, the scheming village shaman who favored the Mohawks, argued against this. Tashmu said that he would go that night to Wizard's Glen (an array of rocks with a somewhat dark and mysterious body of lore of its own) with the Mohawk, to ask the spirits which of the suitors they favored. Instead, he went to the brook and with Yonnongah's help dug out one side so that it was much deeper than the other.

In the morning, Tashmu told the tribe that the spirits had said for them to place the girl in a canoe and float it down the river to where the rock divides it. Nessacus and Yonnongah would each stand on one side, and whichever side she passed the rock on would indicate who she should marry. The canoe was then let go a good distance upstream from the rock. Tashmu, of course, had placed the Mohawk on the deeper side. He was therefore shocked to see that the canoe drifted over to the other side, grounding by the feet of Nessacus.*** Enraged that he had been foiled, Tashmu left the tribe and went east, where he betrayed them by guiding Major John Talcott to the valley (-here history once more pokes its head into the legend narrative, for Talcott is known to have pursued a band of Wampanoag into the Berkshires as part of the last major skirmish of King Phillip's War, becoming the first known white man to enter the area).

In most versions, Tashmu was slain, either by Nessacus or by one of the other Pequot warriors, and the tribe moved on west. In one version, however, Nessacus himself was slain in battle. Stricken with grief, Wahconah leaped to her death from the top of the falls.

***

What lies behind all these legends of love gone wrong, ending in a suicidal lead from a high precipice?

Stories of "Lover's Leaps" are to be found throughout history. The first recorded location of such incidents appears to be a cliff on the southwest side of the Greek island of Leucadia. It was here, some classical sources tell us, that the poet Sappho of Lesbos, and Queen Artemisia of Caria, ended the sorrow of their impossible love by plunging into the sea.

It is a common motif in American Indian lore. Folklorist Jan Brunvand, in his

American Folklore: An Encyclopedia defines the Lover's Leap motif: "Typically, two Indian lovers, often from different tribes, are prevented from marrying because of tribal enmity or taboo; in despair or defiance, one or both commit suicide by jumping off a precipice."

In a paper on lover's leap legends, philosophy professor Phil Hoebing points out that there is no single explanation for the existence of such legends. He voices the opinion that many may be products of the western imagination, and that the proximity of high ledges may be one factor, adding in that tourism may help perpetuate the legend, as it makes a romantic addition to tours of scenic sites.

How do we explain the existence of so many such legends concentrated in one small regional area, though? Can we posit that these stories fulfilled some social function, either for the natives who lived there first, or for later European communities? Or do some real events underlie these occurrences, as the historical details in the case of the Wahconah story, and the physical existence of the rock pile at Monument Mountain, might suggest?

In his book

Suicide Clusters, Loren Coleman demonstrates how accounts of a suicide, when spread (today by modern media forms, in earlier times by oral tradition), can shape the method by which other suicidal individuals, especially in the same community or neighboring communities, decide to take their lives. Perhaps something of this nature took place in the Berkshire Hills, at some point in the distant past. Perhaps there was a spate of such suicides by jumping, egged on by the contagion effect that seems to be at work in cycles of suicide behavior. It may have had nothing to do with doomed or unrequited love, but with unbearable pressures brought on by the incursion of colonial settlers in the late 17th and early 18th century, and only later been remembered in a few romanticized stories.

We cannot know for sure. All we can do is look up at these lofty places, marveling at the way the hills stand sentinel over the horizon, silently holding on to the secrets of their history.

Endnotes:

*There have been a number of accidental deaths at Bash Bish Falls over the years as well. During the 1960's, climbers and swimmers died there at a rate of two or three a year. Swimming is now prohibited, and climbing is allowed only by special permit from the parks department.

** According to yet another local legend, Bryant himself eventually returned to the Berkshires as a ghost.

*** In my favorite twist on this legend, one version claims that after the canoe contest, one of the braves from the tribe found a large twig jutting out of the brook. It occurred to him that it by using such a twig against the mud at the bottom of the brook, it would have been possible for Wahconah to have steered the canoe in whichever direction she chose. He told Miacomo of his suspicions, but the old chief only nodded, smiling.

Selected Sources:

Belland, Debra & Frederick Talarico.

There's no place like home: a journey through the rich legacy of the Berkshires, 2000

Brunvand, Jan.

American Folklore: An Encyclopedia, 1998

Coleman, Loren.

Suicide Clusters, 1987

Coxey, Willard Douglas.

Ghosts of Old Berkshire, 1934

Hoebing, Phil. Legends of Lover's Leaps, 2001Bryant, William Cullen,

1794-1878: Poems-Various other oral and written versions of these three legends.

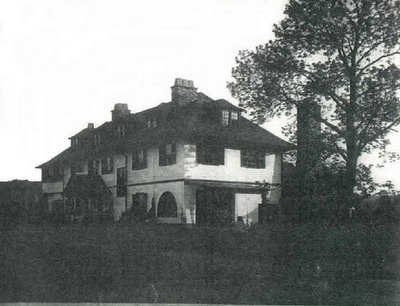

Fernbrook circa 1920 rear of house.

Fernbrook circa 1920 rear of house. High Point circa 1990 (courtesy of Gray Locke)

High Point circa 1990 (courtesy of Gray Locke)