Advocate Weekly

Thursday, April 20

"Sources," Edith Wharton once wrote, ".are not one what one needs in judging a ghost story. The good ones bring their own internal proof of their own ghostliness; and no other evidence is needed."

A troublesome remark for me, certainly, as a significant amount of my time is spent seeking out the sources of ghost stories, and judging them thereby. In her own case, however, her observation proves apt enough: the stories of paranormal events coming out of her Lenox home the last few decades do have a sort of inarguable internal logic.

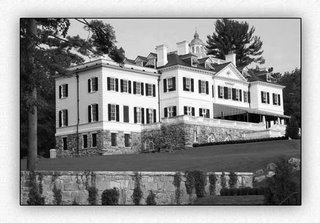

The Mount was built between 1900 and 1902, on a 130 acre tract of Lenox land Wharton purchased for just over $40,000. She based the mansion in large part on Belton House, in Lincolnshire, England, designed by Sir Christopher Wren. The architecture was handled by the firm Hoppin & Koen (not, as is frequently stated, her friend and literary collaborator Ogden Codman, whom she replaced after initial planning for being too expensive), but the lion's share of the credit goes to Wharton herself, whose instructions the architects merely followed to the letter. The house she outlined reflected the sensibilities she had put forth in her own book on the subject, "The Decoration of Houses." She could be said to be an advocate of minimalism - at least by the "never-say-when" standards of the Gilded Age - nonetheless, the expense of the project was extreme. Despite Wharton's substantial wealth, the final touches had to wait until 1905 brought a much needed injection of cash, in the form of "House of Mirth" royalties.

Wharton called The Mount her "first real home," and considered it an ideal environment for writing, which she worked on each morning sitting up in bed, saying that she preferred to keep the practice of her craft from interfering with her other obligations. In the decade that she kept residence at her sprawling estate along Laurel Lake, Wharton completed some of her finest work. In particular, a fair majority of the events and characters in "Ethan Frome," including Frome himself, were directly drawn from local inspiration. While living there with her husband, Edward (Teddy) Wharton - a wealthy socialite born into the same circles as Edith (maiden name Jones, the family referred to in the once popular catch-phrase "keeping up with the Joneses") - she frequently entertained as guests many luminaries of the literary and intellectual world, including Richard Watson Gilder, Howard Sturgis, Clyde Fitch and Henry James.

Wharton sold the property in 1912, as her marriage to Teddy (described by some contemporaries as "charming but dim"), was dissolving. She never returned. It was remarked that in the end Wharton found Paris to be her true "spiritual home." While this may be true, it was The Mount, above and beyond any other location, which in later years would come to be thought of as her spectral home. The property has changed hands half a dozen times since then, but Wharton's presence, both historical and otherwise, has left a palpable and seemingly unshakable mark on the estate.

The Mount came for a time under the ownership of Carr van Anda, managing editor of the New York Times, who in 1943 sold it to Foxhollow School, which had purchased the former Vanderbilt estate adjacent to it a few years earlier. For about 30 years, The Mount served as a dormitory for the girls' preparatory school, and it is during this period that the first rumors of a ghostly presence began circulating. "There were lots of stories," said one former student. " Of course, girls' boarding schools will be girls boarding schools."

Dorothy Carpenter, another alumna of Foxhollow, reported the following: "People use to talk about it all the time.... Every time we'd hear a creak, we'd say it was Edith Wharton's ghost, but nobody really thought it was." Carpenter's perspective on the stories changed, however, when she returned to the house in the early '70s. The house had fallen into disuse by then, and Carpenter spent two months living there alone while she worked on restoration of the ballroom ceiling. One day, she was staring off absently out the window, when she saw a woman in period clothing walking across the terrace. She recognized her instantly from pictures she'd seen, but the version she was looking at now seemed far more vivid, more "alive" than any representation. "At the time, I thought maybe I'd been inhaling too much plaster dust."

As most locals know, in the late '70s The Mount was acquired by the legendary theatre troupe Shakespeare & Company, who occupied the site for more than 20 years. During this period, apparitions and spectral tableaus were reportedly witnessed by some of the brightest luminaries of the regional theater world. Dennis Krausnick, a former Jesuit priest turned actor and director, was one of the first people to enter the building. He reported that while he was working alone in the house, he heard footsteps constantly, but could find no one in the house upon searching. Josephine Abady, former head of the Hampshire College theater department and artistic director for Berkshire Theater Festival, described to one writer how she saw an apparition of Wharton several times while on the premises, and was haunted constantly by a rustling sound not unlike the swishing of a someone in a long dress walking by. On at least one occasion, she saw the Wharton figure in the company of a man who looked very much like Henry James, not knowing at the time that James had been a favorite house guest there.

This same male ghost was reported by none other than Shakespeare & Company founder Tina Packer, perhaps tellingly in the "Henry James Bedroom." Another actress, Andrea Haring, described a supernatural scene of both the Whartons, as well as James, all apparently engaged in conversation. The sheer appropriateness of the idea of The Mount being haunted by both Wharton and James cannot be overstated. Among her other literary accomplishments, Wharton is generally held in high regard as one of the finest American purveyors of the ghost story, who cared passionately about the subject and brought many novel touches to the genre. As for Henry James, well, I won't gush, but "Turn of the Screw" is quite simply, in my opinion, among only two or three other pieces of writing committed to paper contending for the title of greatest horror story ever.

With such a foundation - combined with the building's reincarnations as first a prep school, then theatrical mecca, both highly charged, creative environments - perhaps ghostly sightings were inevitable. Maybe Wharton really was right about ghost stories, after all.

"Sources":

Berkshire Evening Eagle, May 20, 1943

Fitchburg Sentinel & Enterprise May 30, 2002

Myers, Arthur. The Ghostly Register (Contemporary, 1986)

Ogden, Tom. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Ghosts & Hauntings (Alpha Books, 2004)

Owens, Carole. The Berkshire Cottages: A Vanishing Era (Cottage Press, 1994)

--

Joe Durwin is a freelance writer and one possible answer to the question "Who ya gonna call?" Send comments or reports of the strange to joe@durwin.net.